How to make superstores desirable again

Three ways retail marketers can bring the crowds back to out-of-town stores.

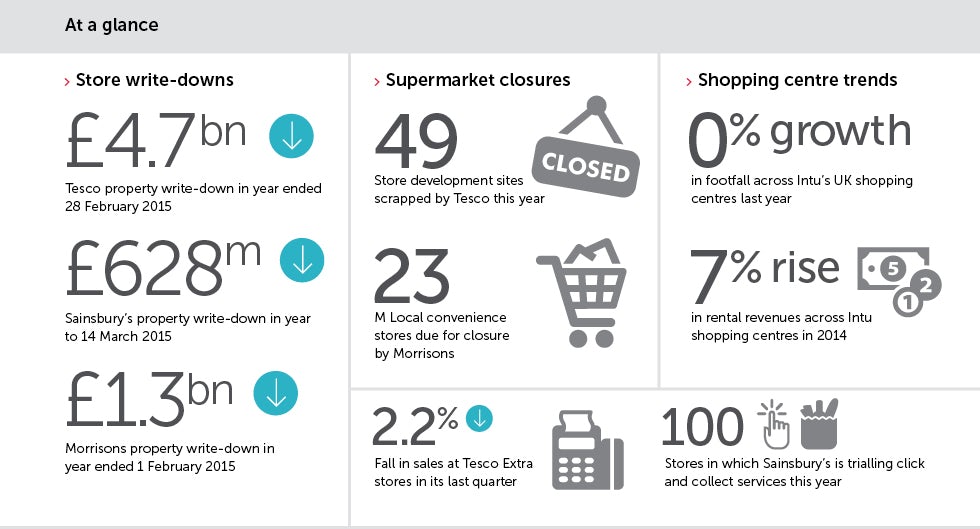

Property has become a millstone for the UK’s floundering supermarket operators.

Last week Sainsbury’s was forced to write down the value of its property estate by £628m as it reported an annual loss of £72m, its first deficit for 10 years. The announcement came two weeks after Tesco took a massive £4.7bn hit on the value of its property as it posted a £6.4bn loss, the worst performance in its entire 96-year history.

The upshot is a need for big retailers to transform the proposition of shopping in a bricks-and-mortar environment. The supermarkets’ struggles may not quite mark the end of the out-of-town superstore, but they could herald a new age where experiences and entertainment become as important as selling merchandise, and where complementary brands share space to create retail ‘destinations’.

Marketers will need to be the architects and communicators of this new proposition, which will represent a significant departure for brands.

“Brands want to showcase their range. Even if you’re not buying in the centre at that time, it will drive online purchase behaviour.”

Trevor Pereira, Intu

Property is not the sole cause of these retailers’ woes, of course, as fierce competition from discounters such as Lidl and Aldi, management failures and falling brand loyalty among consumers have all played a role in hobbling the country’s biggest grocers. But while their boards can appoint new directors, sanction price cuts or introduce new marketing initiatives at relative speed, overhauling a cumbersome and unsuitable store portfolio is a much more daunting task.

The scale of the property write-downs has led to accusations that the big supermarket groups were guilty of short-sighted planning – or worse, hubris – during the pre-recession boom years. By investing heavily in large store developments, it is claimed that brands like Tesco failed to anticipate changes in consumer behaviour such as the switch to cheaper retailers and an increasing preference for top-up shopping at smaller convenience stores.

The reality is more complex. Of the 43 underperforming stores that Tesco closed earlier this year, only seven were Tesco superstores while 30 were convenience stores (18 Express outlets and 12 Metro). The remaining six were stores for Tesco’s non-food business Homeplus. The retailer chose not to close any of its out-of-town Tesco Extra stores, its largest store format. Finding a buyer for these huge sites is much more challenging, so retailers must find relevance in a marketing proposition that highlights the breadth of the offer in these stores.

Similarly, retailers face a big challenge in marketing the convenience store concept and matching it to the locations in which it has been deployed.

Supermarket Morrisons’ recent travails show that opening more convenience stores in town centres is not necessarily a panacea for struggling operators. Despite having bought up large swathes of high street space, including many former Blockbuster video rental units, the company has confirmed plans to close 23 of its M Local stores following the underperformance of several outlets. In March, Morrisons announced a £1.3bn property writedown as it posted a £792m annual loss.

Tom Whittington, retail research director at property consultancy Savills, suggests that in their rush to secure the best high street space, some brands have bought into locations that are either too competitive, low margin, or over-rented. Some small stores have proved to be unsustainable as a result.

He believes the decline of large out-of-town stores has been overplayed and that retailers need to think more creatively about how to adapt these huge spaces. This includes ensuring that the resulting customer experience across store types is consistent with the overall brand promise.

“The sales densities of the big stores are lower than [convenience stores] and they haven’t worked as effectively as the retailers would have wanted them to, but it’s often forgotten that they still make a lot of money,” says Whittington.

“The fact is that they’re not easy stores to get rid of and there are only certain locations where you can look at other uses [for the land], so in a sense the retailers are just going to have to make the best of it.”

1. Repurpose wasted space

Following Tesco’s results last month, chief executive Dave Lewis confirmed plans to devote more resources to improving its out-of-town hypermarkets. Sales at Tesco Extra, which account for 250 of Tesco’s 2,670 stores, fell by 2.2% in the final quarter – a significant improvement on the 6.3% fall in the third quarter and a 7.5 percent drop in the second.

Lewis claimed the improved performance was proof that large stores are “not quite the dinosaurs people have painted them to be”. Being a former Unilever FMCG marketer rather than a retailer by background, and having already taken big and uncompromising decisions as Tesco CEO, his loyalty to the store format is likely to be purely commercial and not the result of any misplaced affection.

Lewis’s turnaround plan aims to make larger stores synonymous with convenience again. This includes simplifying Tesco’s product ranges and boosting customer service with more staff hires. “I think people have been going to more than one shop because nobody has excelled across the board when it comes to the in-store experience; we want to change that,” Lewis said last month.

He also confirmed that Tesco may look to sublet more space to its external retail investments such as Giraffe restaurants, which it acquired in 2013. Although the roll-out of these partnerships has been limited to date, with only 15 Giraffe sites currently inside or attached to Tesco stores, Lewis said he would cautiously explore opportunities to extend their presence as a means of turning stores into destination locations.

Subletting is likely to become an increasingly popular recourse for all retailers seeking to attract customers to their larger stores. In January Sainsbury’s announced plans to open 10 Argos concessions within its stores this summer, adding to retailers like Jessops and Timpson that already have a presence in the supermarket. Sainsbury’s is also aiming to improve the performance of its larger stores by devoting more space to non-food products like clothing and homeware.

Savills’ Whittington suggests that another option could be for retailers to close parts of their poorest performing large stores and turn them into distribution units for servicing online deliveries. While he agrees that retailers will have to test new concepts in order to maximise their stores, he is sceptical of the extent to which hypermarkets can drive footfall by subletting space to restaurants.

“I’m not convinced that people who go for a big family shop with the intention of saving money are then going to want to spend a lot of money on a meal out at the same time,” he says.

Regardless of how brands choose to adapt their larger stores, marketers must think carefully about how to communicate their new proposition to consumers and ensure that it results in an improved experience for shoppers.

2. Focus on experiences

Out-of-town shopping centres are performing better than large supermarket stores in similar locations, but customer growth is minimal here too. Intu, which operates 18 UK shopping centres including the Trafford Centre, Lakeside and Merry Hill, reported 0% growth in footfall last year, following a 2% fall in 2013. However rental income grew by 7% last year and occupancy held firm at 95% as a result of improving dwell times and average spend among shoppers.

Shopping centres’ growth strategy includes extensive experiential marketing activities. This month Intu is running ‘The Big Treat’, a month-long campaign of events, discounts and competitions aimed at attracting families to its centres. The campaign is being advertised through local media targeted to each centre, while Intu has also launched a Facebook app to encourage people to share promotions with their network.

Other initiatives to drive footfall and longer visits include bringing in more casual dining outlets as opposed to fast food restaurants and opening more attractions like Sea Life at the Trafford Centre or the indoor ski slope at Intu’s Braehead centre. The company also recently installed mobile phone charging ports across its centres and improved its free Wi-Fi with the aim of allowing visitors to stream high-bandwidth video.

“It means that if a guy is out shopping with his wife on a Saturday but he wants to watch the test match he can do that rather than having to leave,” says Intu’s commercial and digital director Trevor Pereira.

The company has sought to embrace the growth of online shopping by offering a transactional website that allows people to buy products from some of its biggest retailers. The site receives around 2 million hits per month with mobile accounting for 80% of traffic, suggesting that many customers are browsing online while shopping in the centres.

Pereira reveals that retailers like John Lewis, Marks & Spencer and Next, which all sell via the site, are simultaneously seeking to improve their store presence. “Those brands are the ones that want to have ever bigger stores in our centres because they want to really showcase their entire range,” he adds. “They know that even if you’re not buying in the centre at that time, it will drive online purchase behaviour later.”

3. Put convenience first

Marketers must think carefully about how to create a seamless experience between online and offline shopping and judge whether their approach will deliver a strong return on investment. Offering in-store Wi-Fi or shoppable touchscreens are not cheap investments but they could prove worthwhile if they help brands to meet consumers’ changing needs.

Many of the biggest retailers are putting their faith in click-and-collect, with Sainsbury’s announcing in March plans to offer the service at 100 of its stores. Last October, meanwhile Waitrose became the first supermarket to launch temperature-controlled click-and-collect lockers on the Transport for London network. The trial is currently limited to four small stations in suburban locations, but a spokesperson for the retailer says it has been encouraged by the initial customer response.

In addition Doddle, a company launched last year to provide click-and-collect depots at train stations, claims to be holding talks with over 50 retailers that wish to use its service. The firm has 30 store locations where people can collect their purchases, make returns and send their own parcels. It currently has 12 retail partners include Amazon, Asos and TM Lewin.

Doddle aims to locate its outlets as close as possible to thoroughfares into and out of stations to prevent people having to deviate from their normal route when picking up packages (see Q&A, below). Chief marketing officer Paddy Earnshaw claims the Doddle service is more efficient for retailers than having an in-store area for collecting orders. He predicts that at its current rate of growth, the company will become the UK’s largest click-and-collect service by capacity this year.

“Every single retailer is fighting for market share, so the more time that you can deliver solutions to customers that make the most out of every square foot in your store, the better it is for the customer,” he suggests.

“Click-and-collect stations are eating up square footage all the time. Yes, they offer the opportunity to drive footfall back into stores, but they’re not going to deliver exciting customer experiences.”

Alongside the growth of click-and-collect, retailers look set to continue scouring the high street for convenience locations. In March it was revealed that Asda is planning to launch its own smaller format stores by opening high street outlets in Deptford and Wealdstone, while Tesco has pressed ahead with its ‘food to go’ mini-store concept, opening its second such shop in central London last month.

Whittington at Savills says there remain plenty of good options for retailers seeking to open smaller convenience stores, but urges brands to think carefully about the locations into which they venture. He suggests that brands can continue to thrive after a big property reorganisation, including large numbers of store closures, provided they adapt their strategy to the changing retail landscape.

“Different companies will take different directions – they have to be fluid and entrepreneurial depending on what’s happening in the market,” he says. “There is undoubtedly a big move to the convenience store, and I have lots of positive reasons for thinking this market is a very important and buoyant one.”

Q: How has the Doddle click-and-collect service grown since launching last September?

Paddy Earnshaw: Last Christmas was the first click-and-collect Christmas, as John Lewis called it, and we saw that trend. We were only three months old as a business at the time but the number of people signing up to the service in the lead-up to Christmas was terrific. We’ve got 30,000 members signed up so far and retailer conversations have been very strong too. We’ve been working with them to become part of their online checkout.

The interesting thing with Doddle is that it gives brands reach that they might not have had before because of the unique nature of our locations. Also, because we’ve got dedicated staff and our locations are fully manned, brands are seeing it as an opportunity to turn the last part of the customer experience into a positive.

Q: How do you choose your locations?

Paddy Earnshaw: It’s mainly in and around train stations and we don’t measure it by distance [from the trains], we measure it by seconds. The Doddle store at Finsbury Park station [in north London], for example, is less than 30 seconds from the tube and train entrances. That’s the sweet spot of where we want to set up locations. We also paint on the floor of train stations the route to the Doddle store to help people save time.

Q: How has the Doddle app helped the business to grow?

Paddy Earnshaw: The app allows us to send push notifications and alert people when their parcels arrive in store. When we started the business we thought the parcels might sit on the shelves for about three days. What has actually happened is that it’s taking less than a day for customers to come in and collect their deliveries.

To have such quick turnaround means that we have three times more capacity than we imagined we would in the model. By this summer, with the way we’re rolling out the business, we’ll have the biggest click-and-collect service by capacity in the UK.