Four trends changing the definition of luxury

As wealth is redistributed and the number of luxury consumers rises brands must adapt to meet changing consumer behaviour.

The partnership between tech giant Apple and fashion powerhouse Hermès on a special-edition Apple Watch is a clear indication that the luxury market is evolving.

The association helps Hermès remain at the cutting edge of luxury but perhaps more significantly, according to Marketing Week columnist Mark Ritson, it is a strong signal that Apple now sees itself as luxury brand. “Look at Apple’s price point. Look at their visual merchandising. Look at their creative directors. Look at their executive team. Look at their mythological founder,” he says.

The limited edition Hermès watch will most likely sell out immediately when it goes on sale on Monday, but Ritson suggests the long-term benefit of the association will be far more valuable for Apple, as the deal has the ability to “alter and improve brand equity as part of the process”. In another move designed to strengthen Apple’s luxury credentials, British fashion label Burberry has become the first brand to launch a dedicated channel on the Apple Music streaming service.

This shift towards Apple being seen as a luxury brand is largely driven by the reputation it has earned through the quality of its engineering – something that illustrates just one of four major changes under way in the wider luxury market. Marketing Week sets out to examine each of these burgeoning trends.

1. Quality comes before exclusivity

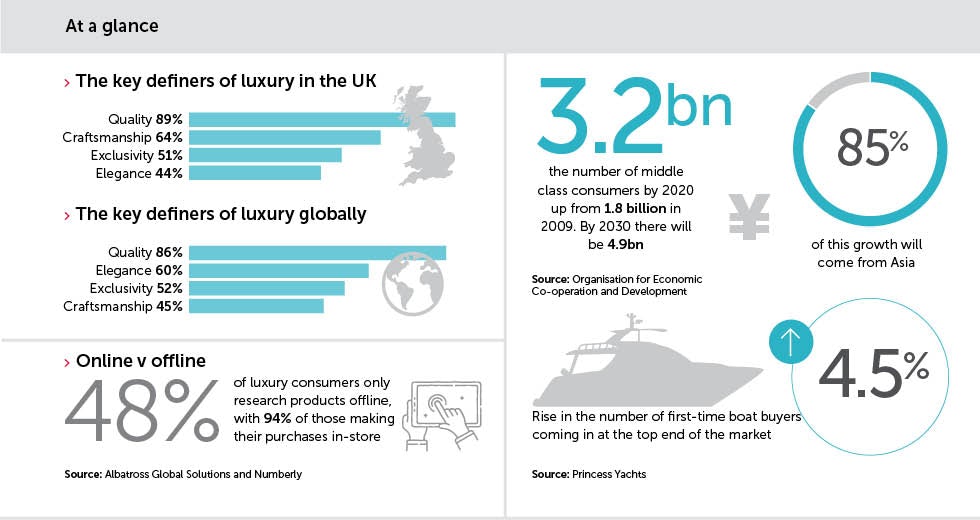

Apple’s partnerships with Hermès and Burberry signal a shift in consumers’ perceptions of what constitutes luxury that is backed up by data from a major new report on the sector. Quality, not exclusivity, is now the key definer of luxury for consumers globally, with 86% citing it as the most important attribute, according to Albatross Global Solutions and Numberly’s fourth annual ‘The Journey of a Luxury Consumer’ report.

Indeed, Apple design chief Jony Ive told The Wall Street Journal last month that he does not consider the Apple Watch Hermès collection “exclusive” and is “not comfortable” with the word.

Quality overtook exclusivity in the report last year as the leading characteristic of luxury, and its prominence continues to rise in 2015’s data, while the role of exclusivity falls back. The number of people naming exclusivity as the key attribute of luxury products drops 15 percentage points to 52% this year, meaning elegance (60%) becomes the second most important attribute for global audiences.

In the UK, quality is even more important than it is for the average global consumer with 89% rating it their top priority, followed by craftsmanship (64%). Again the significance of exclusivity is declining, falling 14 percentage points in the UK to 51%. Elegance (44%) is not as relevant for UK consumers.

“What separates true luxury from the idea of luxury is quality,” says Javier Calvar, chief operating officer at market research firm Albatross Global Solutions.

“As luxury becomes more democratic, exclusivity becomes less important to consumers,” adds Calvar. He suggests this is because of the increase in luxury consumers from China who do not want to show off their wealth, and because for millennials – another group growing in importance and wealth – “luxury is like a membership badge” so they have no interest in something that separates them from their peers.

“We’ve seen a definite shift in our demographic, as has the whole luxury sector,” says Simon Sproule, director of global marketing and communications at Aston Martin Lagonda.

“If you take the total global luxury market, 60% is still baby boomers and above, but the other 40% is ‘Generation X’ and millennials, so [younger people are] a significant chunk of business.”

However, he does not believe the defining attributes that make a product a ‘luxury’ change according to a person’s age. “If you are buying an expensive product, then you’re looking for quality, you’re looking for a story and for something that fits your lifestyle,” he says. For Aston Martin, “it’s about making the car relevant to [different consumers] at that point in their life”.

As a result, the concept of the traditional showroom is becoming less intrinsic to the sales process. Instead, consumers in the luxury car market want to shop for a brand in an environment that is reflective of their lives.

2. Retail footfall is dropping

“People want to experience a brand on their terms, which means they may not necessarily walk into a showroom,” says Sproule. “We have a retail structure, as do all car manufacturers, but we’re seeing an increase in urban locations for car retailing, which is less about selling a car and more about brand experience.”

Concept stores in shopping malls and on the high street, as well as brand showrooms in premium locations in major cities around the world, are therefore becoming more important, as is sponsorship of cultural and sporting events.

In line with this strategy, Aston Martin is taking part in furniture designer Tom Dixon’s Multiplex concept (below), a pop-up department store situated in London’s Old Selfridges Hotel, which has been developed in association with Wallpaper magazine.

“The chance to look at a nice car in a department store may seem unusual but actually it works because people are relaxed as they are out for a day’s shopping. It’s not a hostile environment so it’s a good place for us to be,” Sproule says.

The concept store – an immersive, multisensory look at what the department store of the future might look like – brings together Tom Dixon’s brand with businesses from the worlds of fashion, beauty, art, technology and design.

Dixon created Multiplex to counteract the shift towards online shopping. He says: “It’s getting difficult [for all brands] to do physical spaces. The big challenge that everyone has, and particularly furniture brands, is dragging people off their couches and into real environments to experience real stuff.”

Multiplex is open until 15 October and coincides with London Fashion Week, the London Design Festival, the BFI Film Festival and the Frieze art fair. It includes furniture and lighting from Tom Dixon; an immersive spa experience from perfume brand Haeckels; an installation from eyewear brand Cubitts, where visitors can purchase handmade glasses and view a range of experimental frames made from coal, cement and rust; and a concept car from Aston Martin on the ground floor.

“Keeping a brand as an ‘island’ is an old-fashioned concept,” says Dixon. “The modern world is really about the network you have. We have made a whole new network from different worlds [at Multiplex] and it’s how they overlap and work together that will make them more powerful.”

3. Most luxury consumers are ‘digital natives’

In response to the changing luxury landscape and the rise in wealth of the digitally literate young generations, fashion publisher i-D, which is owned by Vice, has launched Amuse, a global online luxury lifestyle channel designed specifically for millennials.

“A number of luxury brands are still very much on the cusp of getting involved in digital marketing and really understanding it,” says i-D and Amuse managing director Richard Martin, who believes the luxury market is yet to adapt to the new breed of ‘digital-by-default’ consumers. Amuse aims to look at luxury from a different angle that Martin believes is in keeping with today’s aspirational millennials.

“It’s also about redefining what luxury is,” he adds. “Modern luxury could be about experience, curiosity or time, which is becoming ever more precious. We won’t just do articles about expensive products because it’s not about that. We talk about products but we also look at back stories, narrative and why that product is important.”

Martin says the publisher is “trying to break a few moulds” with its approach to video and written content. An example is its take on travel journalism through the ‘Second Gen’ video series, which follows second-generation migrants such as Sharmadean Reid, the founder of Wah Nails, on journeys to their parents’ homeland.

“It creates a highly emotional connection while at the same time looking at travel through fresh eyes,” says Martin. “It has a different level of integrity and is an example of how we look at a traditional topic, such as travel, while making sure we’re building in an emotional narrative.”

Even very traditional luxury brands, such as hotel chain Ritz-Carlton, are realising they need to modernise and refresh certain aspects of their business in order to appeal to younger consumers.

Over the past two years the brand has been on a mission to “make sure everything from food to marketing is appealing to ‘Generation Y’ [another name for millenials]”, according to vice-president of global brand marketing Lisa Holladay. She believes many luxury chains run the risk of becoming irrelevant as they continue to pursue outdated strategies.

As part of the move, Holladay says Ritz-Carlton will update its hotels to incorporate cultural influences that better reflect each individual location and create less formal dining experiences to appeal to “the next phase of luxury travellers, who do perhaps also enjoy boutique hotels and Airbnb”.

The hotel chain, named the world’s most popular luxury hotel brand in a report by consultancy Luxury Branding last week, has also unveiled a new “bolder” logo that it hopes will create better stand-out, particularly in growing markets such as Asia and the Middle East where its brand recognition is lower.

4. Growth of the global middle class

The evolution of the luxury consumer landscape will progress at a faster pace as people’s wealth continues to rise, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. It estimates that the size of the middle class globally will reach 3.2 billion by 2020, up from 1.8 billion in 2009, and it is expected to reach 4.9 billion by 2030. Around 85% of this growth is expected to come from Asia.

“It means that wealth around the world is being redistributed, and when money goes into the hands of people that didn’t have much of it before the relationship those individuals have with luxury brands is very different from those who have been exposed to luxury brands for a long time,” says Calvar at Albatross Global Solutions.

It is something that luxury yacht brand Princess is witnessing. Over the past year, the yacht manufacturer has seen a 4.5% increase in the number of first-time boat buyers purchasing its top-end M-class products, which marketing director Kiran Haslam says “tells me a lot about what somebody entering the market wants in terms of luxury”.

“There is a level of comfort in spend unlike what we’ve seen previously. People are comfortable spending a lot more money than ever before, even within the luxury market segment,” he adds.

Princess deals with a mix of customer types, from people who have inherited their wealth through to self-made millionaires and more “flamboyant” customers who tend to come from emerging market wealth. The latter want “instant gratification”, Haslam says, which can be difficult as boats generally take 12 to 14 months to build.

Growth is coming from younger buyers too. He adds: “A really large percentage of our top-end product customers are between the age of 30 and 50. It’s no longer a retirement plan to buy yourself a yacht to enjoy in your golden years. We have much younger buyers coming through. We saw that at both the Cannes and Southampton boat shows.”

As the number of luxury consumers rises and wealth is redistributed globally, the brands that prosper will be the ones that refresh and adapt to meet the changing consumer behaviour these shifts are creating.

Simon Sproule will be speaking at the Festival of Marketing in November. For more information and to get tickets, visit www.festivalofmarketing.com

Luxury is becoming less of a status symbol in the UK

In line with the fact that exclusivity is becoming less relevant as a defining factor of luxury, fewer UK consumers see luxury products as a status symbol, according to the fourth edition of Albatross Global Solutions and Numberly’s ‘The Journey of a Luxury Consumer’ report.

Nearly two thirds (63%) of UK consumers view luxury purchases as a way to reward themselves and to meet their own personal needs, the largest proportion of anywhere in the world. This compares to just 48% when looking at a global level.

The remaining consumers in the UK see luxury goods as way of promoting their social standing, with 12% classing it as an indicator or social success, 12% believing it is a sign of social acceptance and a further 12% viewing luxury purchases as a status symbol.

Recognition from peers is far more important for consumers globally. Just under a quarter (22%) view luxury purchases as a status symbol, 18% associate designer goods with social success and 11% buy luxury items to gain social acceptance.

This trend is exaggerated further among millennials, 62% of whom make luxury purchases in order to gain some form of social acknowledgment, with one survey respondent from New York stating that luxury is about “being able to show the best version of myself” and “show other people I am playing at their level”.

“In the past, millennials have been accused of being unsocial, lazy and irresponsible but today these people are getting jobs, pursuing careers and becoming socially responsible individuals. They need recognition [of this shift in behaviour] and luxury helps them get that recognition,” says Javier Calvar, chief operating officer at market research firm Albatross Global Solutions.

With regards to the key channels for information and inspiration ahead of making a purchase, the UK is more in line with the rest of the world. Stores remain the main source of communication for consumers (59% global, 58% UK), followed by digital media (58% global, 52% UK).

No matter where information is sourced, however, most purchases are made in stores. In the UK, 48% of consumers only research products offline, with 94% going on to make purchases in-store. This compares to just 13% who only use digital channels for research, 44% of which go on to buy goods online. For consumers who do a mixture of online and offline research (39%), 88% make their purchases in-store, while 12% choose to do so online.